President Obama delivers his speech announcing the final Clean Power Plan on Monday, August 3 (courtesy of Susan Walsh/Associated Press).

Last Monday, President Obama stood at the podium in the East Room of the White House to announce “the single most important step America has ever taken in the fight against global climate change” – the final Clean Power Plan (CPP). As the President noted in his remarks, this final rule amounts to “the first-ever nationwide standards to end the limitless dumping of carbon pollution from power plants” into our atmosphere. The EPA projects that, if fully implemented, carbon emissions from US power plants should be 32% lower in 2030 than in 2005.

Here in Ohio, the rule was met by a mixture of excitement from those of us who want the country to take action on climate change and outrage from those who oppose such steps. Attorney General Mike DeWine joined 11 other attorneys general in a lawsuit to derail the rule, while notorious Ohio coal firm and serial litigant Murray Energy intends to file no fewer than 5 separate suits.

Changes to the final Clean Power Plan that affect Ohio

Given all of this controversy over the CPP, it may be wise to take a step back and consider just how the rule would affect Ohio. Last year, I explored how Ohio fared in the proposed CPP and how the state’s clean energy standards put it on a solid path towards meeting its carbon reduction targets. While that analysis was relevant at the time, we need to revisit it, as the final CPP is different from the proposed version in a lot of ways. For the sake of this post, here are a few of the key changes that will affect Ohio:

- State compliance plan date: Under the proposed CPP, states needed to submit their compliance plans to the EPA by June 30, 2016. The final rule pushes this date back to September 6, 2018, but with a caveat. States still need to submit either a final plan or an interim plan in 2016, but they can request a 2-year extension of the deadline if they meet certain criteria. This matters, as Ohio EPA Director Craig Butler has already stated that he will wait until to submit a plan until he sees how the rule fares in the federal court system, which may take years.

- Emissions cuts to begin later: Whereas the proposed CPP required states to begin cutting carbon emissions in 2020 and continue through 2030, the final rule delays that effective date until 2022. This 2-year delay is important for Ohio as a result of SB 310, as I will explore later.

- Changing the way that emissions reductions are measured: Originally, the EPA planned to measure emissions reductions as the change in how many pounds of carbon emissions a state produces per megawatt hour (MWh) of energy it produced (“rate-based”). But the Agency has now added a “mass-based” approach, which shows reductions in the actual tons of carbon states emit. Additionally, EPA has changed the state-by-state targets to account for the fact that the utility sector operates within 3 broader regions. As a result, Ohio’s rate-based target was strengthened from 1,338 lbs/MWh to 1,190, up to 37.4% from a 27.7%. The mass-based reduction remains at a comparable 27.85%.

- Eliminating the energy efficiency benchmark: The proposed CPP created federal guidelines for state compliance plans that included 4 main building blocks: improved coal plant efficiency, more use of natural gas, increasing renewable energy generation, and improving demand-side energy efficiency. EPA has removed the energy efficiency building block, which has significantly reduced the CPP’s legal vulnerability. Fortunately, EPA did not scrap demand-side energy efficiency entirely. Instead, it will allow states to include it as part of their state compliance plan.

How Ohio can meet its Clean Power Plan requirements

Fortunately, Ohio is well-positioned to meet its emissions reduction targets under the CPP, as multiple analyses have shown.

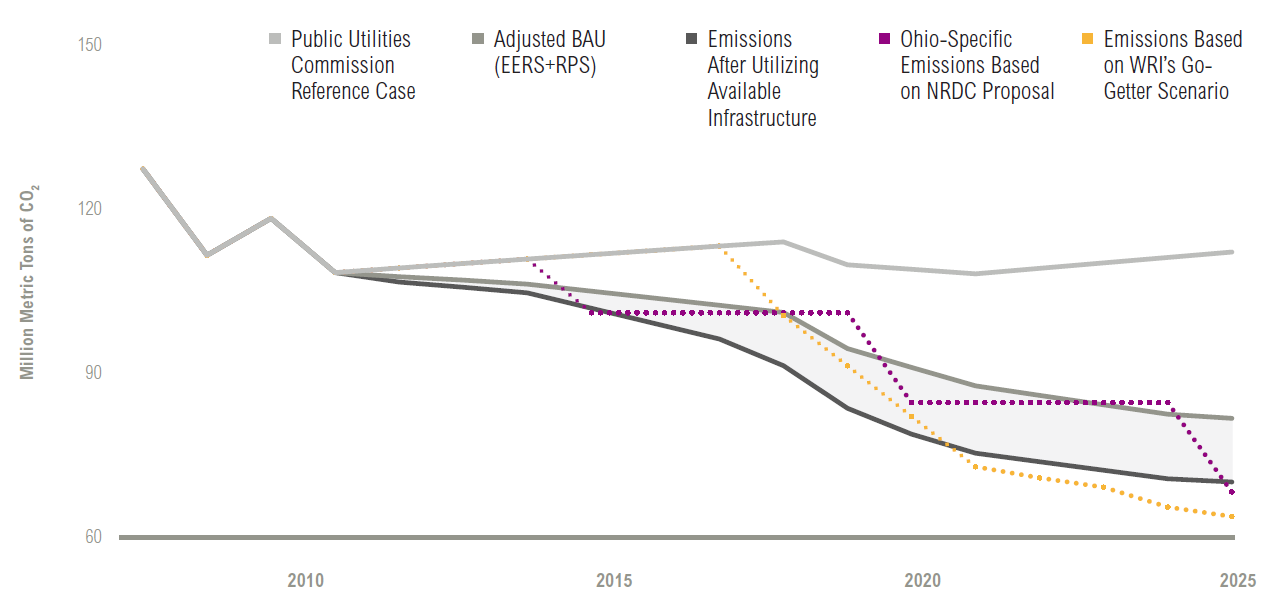

In a 2013 analysis, the World Resources Institute found that, if Ohio fully implemented its renewable portfolio standard (RPS) and energy efficiency resource standard (EERS) that the state passed nearly unanimously back under SB 221, it could cut its carbon emissions by 17% through 2020.

WRI’s analysis also calculated the emissions savings from the other 2 building blocks in the CPP. It estimated that Ohio could cut its emissions by 7% by 2020 if it increased the operating capacity of its existing natural gas fleet (building block 2). The state could further cut emissions by 2% if it improved its coal plant efficiency by 2.5% (building block 1). Combined, these four actions would get Ohio to a 26% cut by 2020, before the CPP’s requirements even kick in. And if Ohio continued to implement its EERS and RPS beyond their current end date, the state would be able to meet and exceed its required carbon targets.

Ohio can cut its carbon emissions by up to 24% through 2020, depending on the policies it implements under the Clean Power Plan (courtesy of World Resources Institute).

SB 310 will make increase the costs of compliance

While Ohio is currently in decent shape, SB 310 will unquestionably make it more difficult and more expensive for the state to comply with the CPP.

The two-year freeze on the RPS and EERS will deprive the state of renewable energy and energy efficiency gains that it could count towards future benchmarks. Though it pushed back the date when states have to demonstrate emissions cuts by 2 years, EPA wants to encourage states to reduce their carbon emissions before that point. Accordingly, the final CPP creates a Clean Energy Incentive Program (CEIP), which allows states to get credits for renewable energy generation and energy efficiency measures taken in 2020 and 2021 and apply these to reduction targets in subsequent years. For every 1 MWh of wind or solar that a utility brings on line, it will get a 1 MWh credit towards future emissions reductions. And for every 1 MWh saved through energy efficiency projects in low-income communities, utilities will get a 2 MWh credit.

Because SB 310 freezes Ohio’s RPS and EERS for 2015 and 2016, the RPS and EERS benchmarks will be lower during 2020 and 2021. RPS benchmarks will decline to 6.5% and 7.5% from 8.5% and 9.5%, respectively, while the efficiency requirement for 2020 will be halved to 1%. According to projections from the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (PUCO), the state’s major electric utilities would have generated almost 25.9 million MWh of renewables in 2020 and 2021; however, thanks to SB 310, this number will fall by nearly 25% to 19.4 million MWh.

The freeze will also cut into the amount of low-income energy efficiency projects carried out in the state. From 2009-2012, Ohio’s major electric utilities realized 55,084 MWh in energy savings from low-income projects. This accounted for just under 1% of total savings. Based on estimates from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), Ohio was on course to save 56,410 MWh from energy efficiency in 2020 and 2021 before SB 310. Using revised energy savings from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), which account for SB 310’s effects, this number would fall to 46,866 MWh. Because these savings get double credit in the CEIP, Ohio will lose out on 19,048 MWh of emissions reduction credits (ERCs).

All told, the 2-year freeze on Ohio’s clean energy standards enacted under SB 310 will cause the state to miss out 6,476,386 MWh of ERCs. If we assume that each of those MWh would have offset a unit from a fossil fuel plant, we can estimate how many tons of carbon emission reductions the state will lose. EPA has calculated that Ohio’s power plants release 1,900 pounds of CO2 per MWh; as such, Ohio will lose ERCs worth roughly 6,152,567 short tons of CO2. Applying a social cost of carbon at $40 per ton means that this one effect of SB 310 will cost the state more than $246 million.

But that doesn’t account for any potential reductions in the RPS and EERS benchmarks. The bill’s language makes it perfectly clear that the Ohio legislature intends to “enact legislation in the future… that will reduce the mandates.” Any future reductions to these clean energy standards will make it that much harder for Ohio to comply with the Clean Power Plan.

What should Ohio’s elected officials do?

Clearly, SB 310 carries a big price tag for Ohio. The state’s elected officials should take action on three fronts to address this issue.

First, the legislature needs to pass a bill restoring Ohio’s clean energy standards as enacted under SB 221. It should not wait until the freeze comes to an end on December 31, 2016. Instead, legislators should use the final report from the Energy Mandates Study Committee, which is expected to be released this fall, as a reason to restore the standards effective January 1. Interestingly, OEPA Director Butler told Gongwer (subscription required) that, despite his reservations, he realizes restoring the standards from SB 221 would help Ohio meet its emission reductions targets. Beyond this step, however, the legislature should look to pass a follow-up bill by the end of the next session that will extend and, preferably, strengthen these standards through at least 2030.

Second, Ohio should begin exploring how it can partner with other states to form a regional carbon trading system. The final CPP explicitly allows and even encourages states to pursue this route. Several Midwestern states have been meeting under the auspices of the Great Plans Institute to discuss this option, but Ohio has conspicuously been absent. It would be in the state’s best interest to work with its neighbors in order to lower the cost of compliance.

Third, Ohio needs to double down on low-income energy efficiency. According to Policy Matters Ohio, the state currently weatherizes roughly 7,000 homes per year. This number accounts for just 1.5% of the households in the state who seek emergency assistance for their utility bills each year. Not only will ramping up low-income weatherization allow the state to get additional credits through the CEIP, it will generate tangible benefits. Every $1 million invested in weatherization leads to the creation of 75 jobs.

Ultimately, SB 310 has cost Ohio considerably, but it’s not too late to mitigate those effects. Every day that Ohio continues to languish under this bill will continue to add to those costs. It’s time to act.

– Tim Kovach, Executive Committee Member